This article is a collaboration with Peter Braun of Armbanduhren Magazine in Germany, with special facilitation by our special correspondant, Dr. Frank Müller of The Bridge to Luxury. The article has been published in Issue 1 of Armbanduhren for 2021.

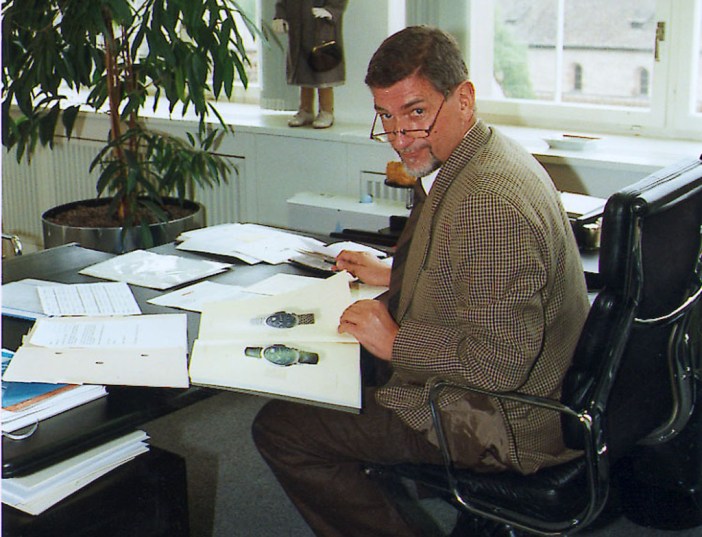

Reinhard Meis is an instrumental player in the watchmaking industry. He was particularly important in the design of the first generation of watches by A. Lange & Söhne, working with Günter Blümlein on the guiding design philosophy. And yet, most collectors do not know him, as his work is mainly behind the scenes. We caught up with him and managed to get him to talk to us about his work and the design of the early Lange wrist watches.

In Conversation with Reinhard Meis

Historical backdrop

When did you discover your love for watchmaking? Tell us about your career.

How I became a watchmaker is a long story. Let us begin with my father. He was trained professionally a mechanical engineer , but he settled to do agriculture on a farm in the Mecklenburg region (in the former communist GDR), where he grew his own food. He had inherited a house in Solingen from his uncle, and along with it a watchmaking shop and workshop. In our family, we said that one of us would become a watchmaker sooner or later and take over the business. The situation in Eastern Germany forced my father to give up the farm in 1951 and to leave the GDR, heading westward via Berlin. The housing situation in Western Germany at that time was difficult to say the least. The family had to split up to stay with relatives: three of us went to Hamburg, two to Stuttgart and I went to Wiesbaden. I was 11 years old then and lived together with three sisters who were school teachers.

One day after breakfast, one of the sisters Johanna pulled out a small gold pocket watch from her purse and asked me: “why doesn’t it work anymore?”. I opened the two rear covers and was surprised to find such a beautiful little mechanism. Although fully wound, it didn’t make any sound. Aunt Gustel handed me her looking (reading) glass, “this shows you more”, she said. I felt like a real watchmaker, and I discovered a few hairs blocking the balance wheel. Since we didn’t have pliers or tweezers in the household, aunt Hilda gave me some sewing needles to poke around between the wheels. I saw a glass with honey on the breakfast table, and something went “click” in my head: sticky! Picking up the hairs with a drop of honey on the ear of the pin did the job, and after removing the last hair, the balance wheel began to swing, slowly at first, but soon at a steady pace. The ladies were enthusiastic and called me a watchmaker. I felt very proud that day, and maybe this was when I decided to become a real watchmaker. I reckon it was my fate.

In 1956 I started an watchmaker’s apprenticeship in Minden, and went on to complete the apprenticeship in Eutin. In my journeyman’s exam I scored 2 out of 2 for manual dexterity and oral capability. I had already received national excellence awards in my second and third year before. After my first journeyman’s year I wanted to go to Johannesburg in South Africa together with a colleague of the same age. But my application was turned down because I hadn’t done my military service yet. So I had to join the Bundeswehr, where they put me – the watchmaker – in the repair shop for tanks and armored vehicles, lifting and shoving gun turrets, engines and track chains and the like for maintenance works.

After my service I came back to watchmaking. But within one year I realized that repair watchmaking was not for me. The work was laborious and involved mainly taking movements apart, lubricating and reassembling them. Often doing two in each morning and another two in the afternoon. I wanted to dig deeper into the watch technology.

Watchmaking and writing books

So in 1967 I took up my studies in Micromechanics and worked a few years as a technical designer in various companies, until I got a job as Technical Assistant in the Physics Faculty of the University of Konstanz. This was much closer to what I really wanted. But I always kept an eye on the watchmaking scene and I realized the decline it underwent. By then the quartz revolution had started, and I thought that Fine watchmaking was about to disappear. Since lifeblood of work at the university was research, writing and publishing, I said to myself “well, maybe I should write a book, too: about watchmaking and technology.” I thought my generation would be the last to have learned watchmaking from scratch, in a workshop, and that everyone coming after me would have to rely upon what has been published, since they wouldn’t be able to learn this first hand.

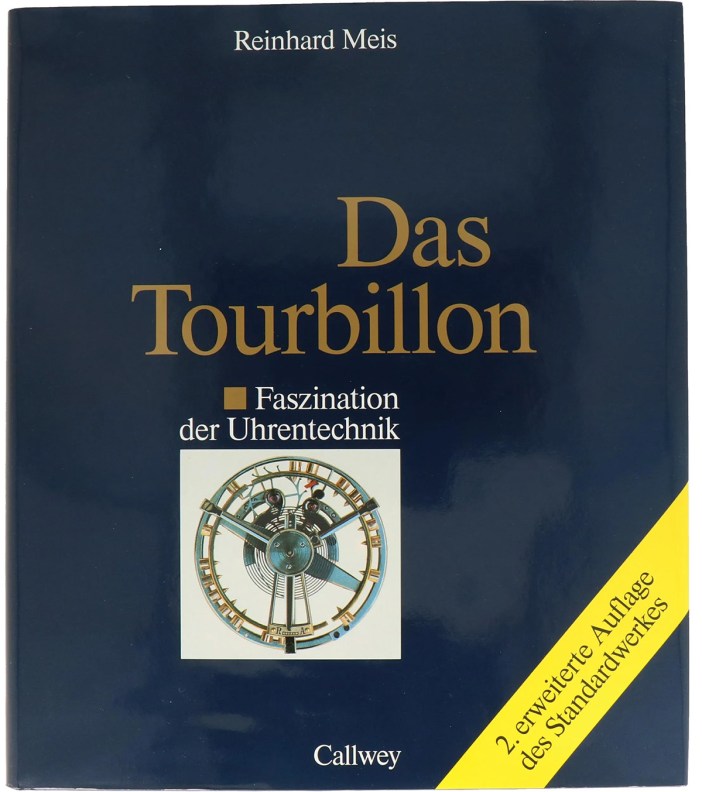

My first book (Die alte Uhr, in two volumes) was published in 1978, followed in 1979 by Taschenuhren, in 1985 by IWC-Uhren and in 1986 by Das Tourbillon. Through the book IWC Uhren I had the first contact with Günter Blümlein, then CEO of IWC Schaffhausen.

A. Lange & Söhne and Günter Blümlein

In 1990 Blümlein rang me up and asked for two copies of the book Das Tourbillon, one in German, one in French. Two weeks later he invited me to Schaffhausen. I was at his office at 9 o’clock in the morning, with pen and paper in front of me. He had my Tourbillon book lying in front of him and he was full of praise for the many technical and perspective drawings on driving and winding mechanisms and tourbillon cages. He questioned me on technical details of tourbillons to find out whether I could reproduce this kind of pencil drawings in 3D on a computer aided system – which of course I had to deny: “I grew up with pencil, ruler and eraser”, I said. He chuckled, and so did I.

He then told me that he was about to resurrect the ancient German watchmaking brand A. Lange & Söhne. His plan was to do this to target the highest levels of the market and asked me whether I had the time and interest to help him to transcend the virtues of excellent pocket watches into modern wristwatches under the Lange brand. He suggested that we could meet on a weekly basis and discuss. I had already expected something like this and brought some sketches of a dial of a complicated watch. We scribbled more sketches during our conversation to point out our ideas on how such a new watch should look. I soon realized that he did not want another Rolex or Patek Philippe, but a completely new watch face for a high-class timepiece. It was Germany vs. Switzerland. We furiously scribbled on, filling more that 10 pages with our visions. It was 7 p.m. when I returned home, my head buzzing like a beehive. Full of ideas and excitement!

Before I left, I had promised Blümlein to speak to my professor. If he would let me go, Blümlein would have to employ me. There was no turning back, as I was about to quit a secure, well-paid job. Blümlein responded that this went without saying. So on February 1st 1991 I began working for Günter Blümlein in Schaffhausen.

The Lange Design Philosophy

Do you see yourself more as a product designer or more as a technical designer?

The best prerequisite to designing an beautiful watch is to master both disciplines. The product designer sketches a beautiful dial and asks his technical designer whether it is feasible. He has to wait for an answer, unless he is a technical designer himself and can respond to the question immediately. So in this standard example, the product follows the design.

A (new) watch first needs a face. The face of a Lange watch is its outer appearance. It takes on the personality, and becomes its corporate identity. The dial consists of many detailed elements, such as hands, indices, layout logo and placement of other texts, etc. And it is important for each element not only to stand on its own, but in relation to each other. I mean, what good is there in to have a delicate nose and place it under your arm, or a beautiful ear on the back of your neck or shining blue eyes in the corners of a mouth?

Does form follow function or does function follow form? When you think of your creations like the Lange 1, Langematik or Datograph, how did you resolve your inner conflicts when design, functionality and feasibility were conceptually contradictory?

The face of a watch is not only its dial. It also needs a clearly distinguishable frame, i.e. a watch case. It is the complete watch with case, dial, hands, strap and buckle that make a Lange watch.

Only when all the details of the watch have found their place, when their proportions are aesthetically pleasing, does the new face appear to be sensual and harmonic. This is when the watch has found its soul. In addition, any new creation must not be a standalone product; it is the start or extension of a conceptual line within the Lange collection. Any product line must radiate from within; there must be a thread that can be drawn from product to product to let them appear as part of a big network. Because any one thread is connected to all the others, the (intended) recognition of any watch as part of the network is imminent. You must have this network in mind, when you develop your ideas for a new watch, and knit the right threads.

Any musician can produce sounds, many musicians together can play a tune, but it is only under the guidance of the maestro that music becomes a symphony. The conductor applies his own personal style to make the piece they perform a distinguished work of art unlike any other.

In the composition of the abovementioned details, the dial plays a major role, because it creates the basis for the new movement to be designed. Every movement Lange uses is designed new, from ground up. Thus it must adopt the clarity of the product line, because it will be visible through the glass case back.

In this sense, the Lange watch is designed from “outside in”, a principle which departs from the established Swiss method. The Swiss technical designer presents his movement to the product developers, who then design the dial to follow the positioning of the hands and indications. If these positions do not suit the product designer’s needs they will have to compromise. Compromises in design – both technical and aesthetical – always create mediocrity, and Lange should not by no means be mediocre. This is why I repeat: The product must follow the design, and not vice versa.

The creative act happens in the head of the product designer; he alone shapes the watches’ face, according to the established corporate identity, and creates the product as a whole. When there are many designers involved, one of them – the best, stylistically most confident – must take the lead and make sure the rules are respected for all future projects – and intervene if necessary. The technical designer then has the responsibility to create the technical basis for this new product and to develop it for series production.

Thus the product designer is charged to deliberately focus on recognition of the Lange character as his foremost principle. Even the smallest detail has its designated place and interacts/cooperates with other details to create this instant Lange recognition.

“to be different, you have to tread new paths

to be precious, you must only use noble materials

to be unique, you must know your competition

to be useful, you must be able to imagine the application

to be functional, you must master the technology

to be aesthetic, you must create a space for beauty”

These six qualities were my reasons and guidelines for the creation of a new Lange product, and they lead my hand when I designed it. “If you are not busy with constantly being reborn, you are busy with dying”, a famous musician (Bob Dylan) once said. If you want to be on top of the watch business, you better keep these words in mind. The product must be recognizable through its details. New technologies may demand new ways, but style must remain.

Of course you can identify individual details which are typical for a Lange watch. These elements could be:

- Dial, appliques, hands, date window, typography of words, numbers and logo

- The typeface I developed out of a normal printing font by slightly widening the characters to give them more substance.

- Watch case, bezel, caseback engravings, lugs and crown have been specially designed for the new Lange watches.

How would you describe the collaboration with Günter Blümlein?

Mr. Blümlein was a well-known figure in the watch world. He knew all the CEO’s by their name and was familiar with most of the models in their collections. There he had a clear advantage over me. But after he had recognized my book on tourbillons, he respected my technical advantage over him. So we were very respectful with each other, calling us by our family names Mr. Blümlein and Mr. Meis. He was the boss, and I was his “prolonged arm”, as he often introduced me to others. There was not a single harsh word or argument in the ten years that we worked together. On my first Baselworld he sent me through the halls to take notes on the all the technical and stylistic novelties.

How did the concepts for the Lange collections evolve, how was the process of decision?

Mr. Blümlein reserved the right of a final decision. Out of my dial propositions he chose two per model, showed them – among others – to his secretary, who had developed a very good taste for watches, asked for her opinion and sent the sketch she had rejected to the prototype department. From this I learned that he was very keen on making his own decisions. If he decided on a proposition, which I didn’t particularly like, I had lost the game. But because as the one in charge I also wanted to have my will. So next time, when I personally favored example B, I mentioned and suggested example A, and promptly Blümlein would react and choose example B, just to have it his way. So he was the decider, but at the same time I had my will. And everybody was comfortable with that.

The Lange 1, Saxonia, Arkade and Datograph

How did the idea of the Lange 1 emerge?

One morning Blümlein came into my office and put a small ladies’ watch movement with a very large date indication on my desk: “Can we use such a date also in a gent’s watch?” I asked him to leave me the movement for a few days to check its functions. I couldn’t find out who had built this movement, but I thought a small ladies’ watch movement with a large date would be very Lange-like, as nobody on the market had such a big date indication. But to use it only in a ladies’ watch was a waste in my eyes. So I began thinking of an gent’s watch with 39 or 40 mm case diameter and an big date window somewhere on the dial, so there would still be room for additional indications or features. After some discussion we decided on an outsize date – eccentric where possible and sensible – and a second spring barrel giving four days of power reserve as a key feature for all Lange watches.

Editor’s note: the design for the outsized date came from a patent registered by Jaeger-LeCoultre, which then was also headed by Blümlein, who had mandated that it was to be used exclusively for Lange. It was only after he passed away in 2001, when JLC started the use of the big date invention.

They say you and Mr. Blümlein drew the first sketches of the Lange 1 on a paper napkin in a restaurant – is that true?

Of course Mr. Blümlein and I have not designed the Lange 1 in a pub or restaurant! But we may have used paper napkins or tablecloth to scribble adventurous ideas. We also discussed other brands and technologies during lunch or dinner.

Was your first design for Lange the Lange 1? And if so, did the Lange 1 become the “mother” of Lange design, from which the three other watches derived – only with technical alterations?

No. Before I started design work for Lange, I designed two movements for other brands. These were not yet committed, so I could bring them to Lange. This gave me, the newcomer, quite a big reputation and respect. My book “Das Tourbillon” had already been published then and was well received.

The Lange 1, Arkade and Saxonia were developed simultaneously, since they all had the same presentation date and we all worked on several projects at a time. Calling the Lange 1 “mother of Lange design” is a little exaggerated, I think.

Which models were you responsible for? All watches within a given time span or were there different people responsible for different projects?

I was hired as “special executive commissioner for traditional watchmaking” and therefore was responsible for all product design at Lange. By October 20, 1996, I had completed 40 dials which were sent to the prototype department and had them approved for production.

Which model are you particularly proud of?

I mean, we were developing great new things. Just listen to the words “outsize date” or “tourbillon” resounding in my head in every technical meeting. We hadn’t decided on the execution yet, but the words were out, and finally the new mechanics found their way into the Lange 1 Tourbillon.

What about the Datograph?

Mr. Blümlein never got tired saying that we needed a chronograph. A chronograph is a very demanding piece of mechanics. I had acquired several chronograph movements to learn about the functions and kinematics. As a preparation for a Lange chronograph I started drawing a 10/1 scale sketch with all the levers, springs, column wheels, screws and other components highlighted in different colors. It was to have hours, minutes and small seconds for the time and on the back side the chronograph seconds and the minute register. I thought a jumping minute register would be technically interesting, but I also knew the design difficulties involved to make this function fool-proof.

To do this, it would be necessary to make the jumping point of the counter fully and individually adjustable. With conventional chronographs the jumping points of two reset hearts can only be adjusted by shifting or turning the hearts on the chrono center wheel in relation to one another. This may require several attempts, always dismantling and reassembling the whole thing. If you had an adjustable minute counter, accessible from outside without having to take the movement apart, this would save assembly time and enhance the precision of the adjustment. The adjustable jumping point is patented and will only ever be found in a Lange.

Which watch you designed would you consider your most beautiful?

This is not something you ask a designer. He would have to admit that he creates beautiful and less beautiful things.

OK, which was your technically most aspiring creation? What is aspiration? A minute repeater, a tourbillon or a chronograph?

For a technical designer all watches with our without complications can be aspiring. Of course you must master all these complications to make technical decisions. But this is our job.

If you had no limitations in time and cost, which watch would you have liked to design?

We have had it all in pocket watches already. The sheer dimensions of a wristwatch movement will not allow to unite all known complications in one watch case. Even with new technologies this requires space.

What characterizes the perfect watch?

Chronometric precision, a beautiful movement and a typical Lange look. Although I must admit that Jaeger-LeCoultre, Patek Philippe and Vacheron Constantin have their perfect watches.

Is there a historical watchmaker who you would call your inspiration or role model?

Well, in my work I don’t stick to model examples. Of course I admire my predecessors. But as a creative person I prefer to think myself.

We heard that you used to draw movement components on a piece of paper, color them and cut them out to test the kinematics of the design. Would you advise today’s designers in times of CAD/CAM to do the same?

Indeed, I used to test new mechanisms with models made of paper or cardboard. Positioning of hands, date discs, power reserve mechanisms or moon phases. I always carried a pair of small, curved scissors and a cutter knife in my drawing pouch. Of course you cannot evaluate the function of a gear train, but visualize dimensions and proportions. I encourage young designers to draw a sketch by hand, when they have a new idea. Hand drawings surely help to visualize your thoughts.

25 years of Lange – did you expect such a huge international success?

Of course, when you develop something new (watches, for instance), you have big expectations. Otherwise you would not put so much effort into the product. And you always want to be better than your competition.

Philosophical conclusions

What does time mean to you?

In principle time is the distance between two occurences. We have the choice between inner time (heart, lungs, kidneys, liver), on which we have no influence, since it follows an inner rhythm. And then there is an outer time.

How do you define this for yourself?

We have a certain influence on this outer time. We can divide a day into 24 hours for example or build a watch which signals us every hour where to meet. I am always short of time. I must organize my day by the hours and minutes, every day.

Do you believe in life after death?

My father was an engineer, I am an engineer. I am happy whenever geologists dig out a skull of somebody older than “Ötzi” (a well-preserved frozen corpse found in the Austrian alps, 5300 years old). Because that means that there have been many before us, and we have gradually evolved into what we are now. Otherwise we would have had only Einsteins, how boring! Believing in evolution is our path, whether we believe in God or not. It is easy to blame for everything we don’t understand. Where do all the dead live once we buried them?

When do you specially appreciate and enjoy time?

When I wake up in the morning and have the whole day in front of me, with no obligations or meetings. Then I can decide myself what to do with my time.

What is your opinion on Smart Watches?

For the last 25 years I have tried to find mechanisms my colleagues haven’t thought of yet and maybe have them patented. But there comes a point when you can’t think of anything new. And all of a sudden there are these digital natives, wearing miniature smart phones on their wrists. And these devices can do anything our watches are capable of, and much more. The development of a modern design for these smart watches has only just begun. Soon you will not need a crown or pushbutton to select a function. You simply slide up your sleeve, ask “what’s the time?” and the smart watch will answer “it’s seven o’clock”. Editor’s note: it exists. Ask Siri!

LIGA, 3D printing, silicon – what do you think of these new technologies?

With LIGA, 3D printing and the use of the properties of silicon development has only just begun. We will have to wait and see, whether AI will lead to better watches. Traditional watchmaking art will disappear, and what will remain – well, only time will tell.

What would you have liked to ask Ferdinand A. Lange?

“What time is it?” Then he would have pulled his watch out of his pocket and we would know what the fashion was.

2 Comments

Reinhard Meis – to me one of the giant designers in modern watchmaking. Likely the most complete I have met being able to master the whole “package”: creating beautiful watch designs, defining wonderful movement aesthetics while being able to invent innovative complications, too.

Thanks Frank for pushing us to do this project and helping to facilitate contact with Meis.